At 6:30 a.m. on December 11, Bianca Censori’s BIO POP debuted via livestream from Seoul, immediately establishing itself as both spectacle and provocation. The opening scene was deceptively simple: Censori, dressed in a full red latex bodysuit, moved through an all-metal kitchen, methodically “baking” a cake. The gesture felt familiar, almost mundane, yet unmistakably theatrical. When the cake was wheeled beneath a red cloche into an adjacent dining room, the domestic scene collapsed into something more unsettling. Masked women, seemingly sculptural at first glance, were revealed as live performers restrained inside medical crutch–like furniture designed by Censori and produced by Ted Lawson.

The cake, as Censori’s statement insists, was not meant for consumption but as an offering. Here, the kitchen becomes an altar and domestic service is reframed as ritualized performance. The performers, dressed in nude latex pieces by KidO Shigenari and molded to resemble Censori herself, further blur distinctions between object, body, and author. The effect is deliberately ambiguous: a space oscillating between reverence and discomfort, care and control.

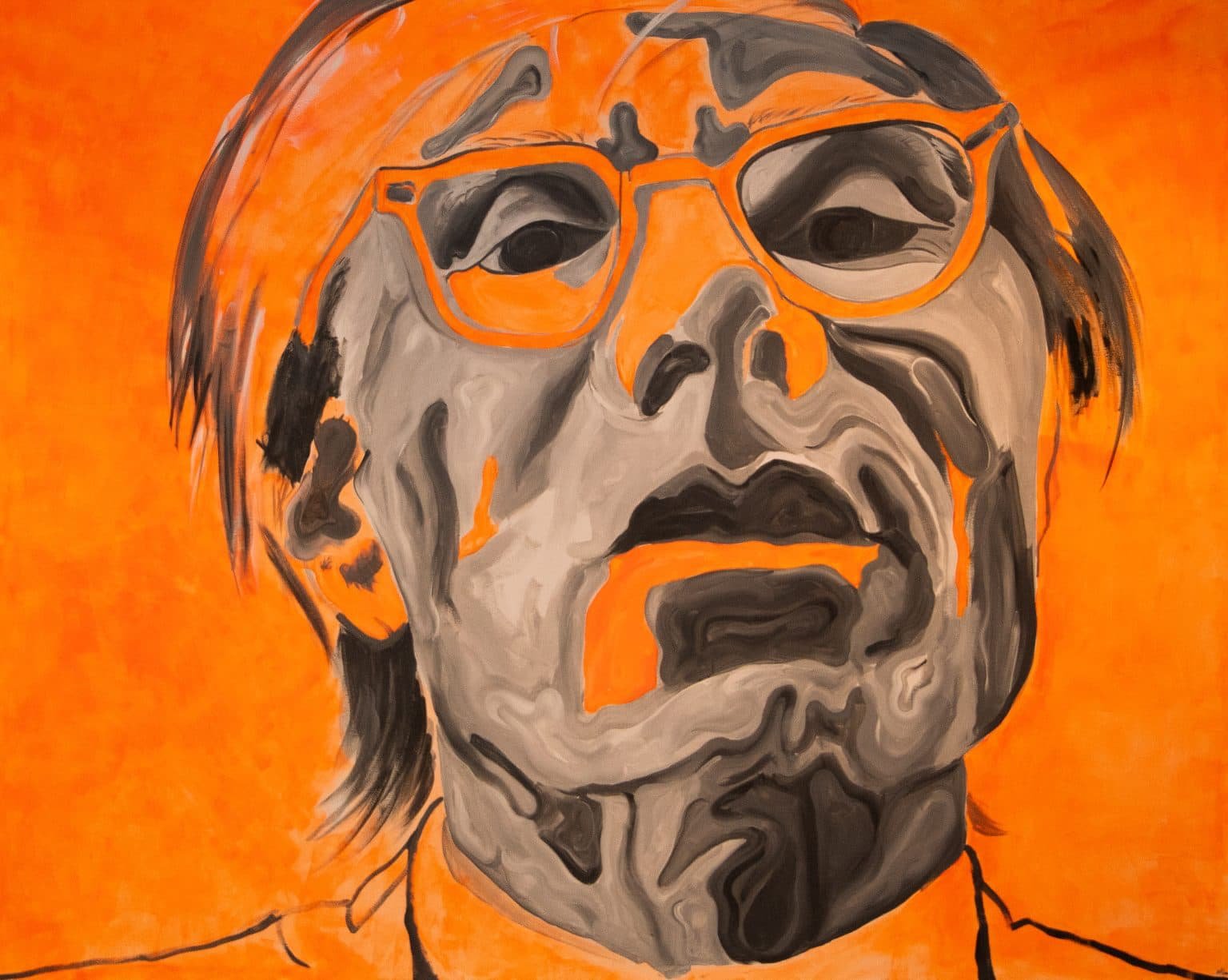

Censori’s public persona inevitably colors the reception of the work. Known as much for her near-nude fashion choices as for her background as an academically trained architect, she has become a lightning rod for debates around agency and visibility. BIO POP leans directly into these tensions, asking whether the body on display is empowered, exploited, or both. Rather than resolving these questions, the exhibition amplifies them.

Domesticity sits at the conceptual core of the project. Described by Censori as “the mother of all revolutions,” the home is framed as the first site where bodies, behaviors, and hierarchies are shaped. Furniture becomes prosthetic, ritualistic, and oppressive at once: chairs, tables, and lamps incorporate sculpted replicas of the artist’s body in contorted or suspended positions, evoking both design objects and reliquaries. Critics have noted echoes of Anna Udenberg’s prosthetic aesthetics and Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen, situating BIO POP within a recognizable feminist lineage.

Yet repetition may be part of the point. BIO POP does not claim originality so much as insistence. It functions as the opening chapter in a planned seven-part cycle unfolding over seven years, centered on themes of confession, sacrifice, and rebirth. Censori remains elusive in addressing the work directly, often responding in the third person as “Bianca.” The refusal to clarify feels intentional. In BIO POP, meaning is not delivered; it is staged, withheld, and contested much like the domestic roles it seeks to expose.