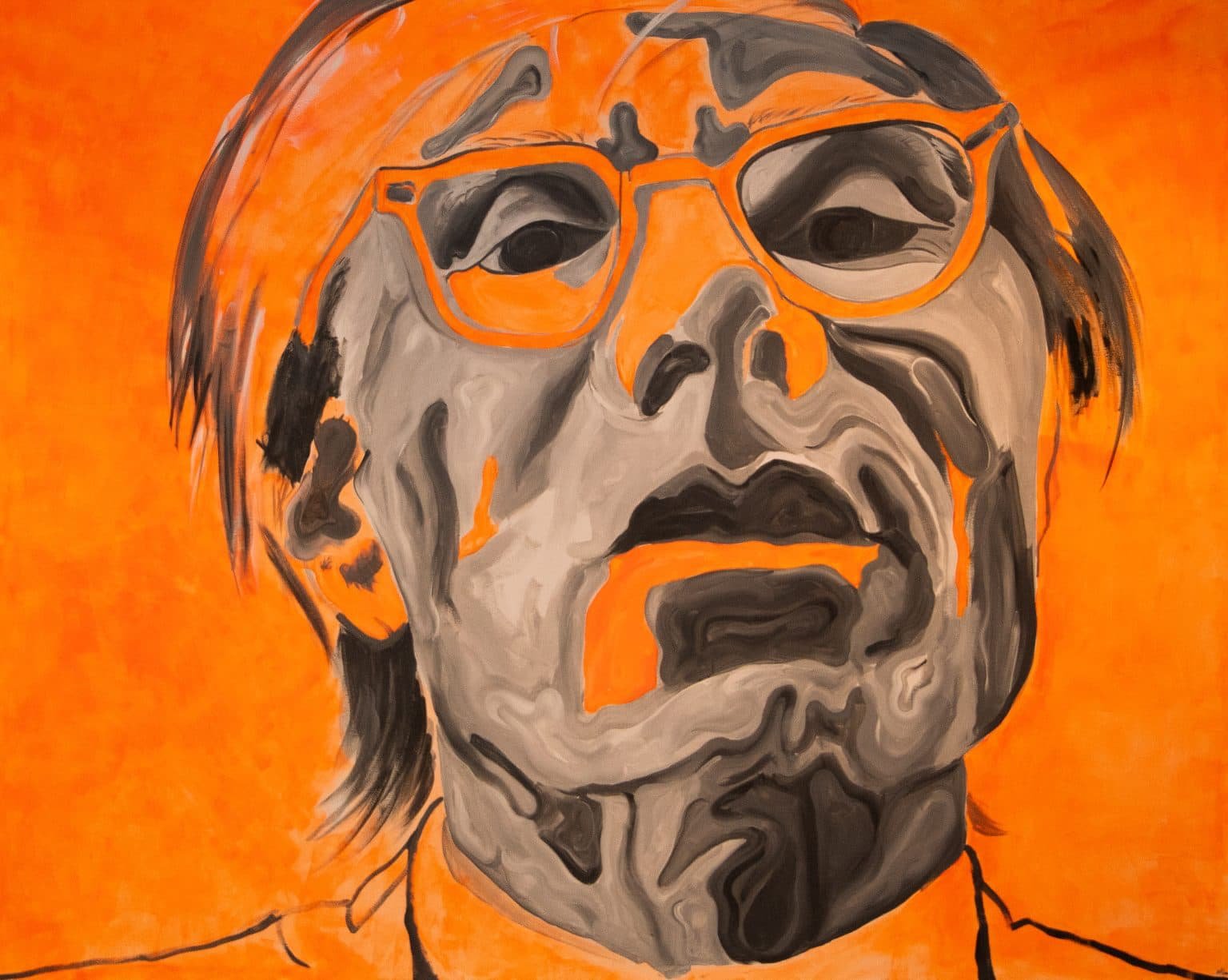

Stepping into Awol Erizku’s visual universe feels like entering an expanding ritual. His work isn’t meant to be merely seen — it’s meant to be invoked. Based in Los Angeles, the multidisciplinary artist has become one of the most visionary voices of his generation, reshaping how Black identity is viewed, perceived, and felt in contemporary art. His self-coined approach, “Afro-esotericism,” blends ancient symbolism, urban culture, and spiritual depth into a language that vibrates beyond gallery walls.

His most recent exhibition, “X”, shown at the Sean Kelly Gallery and the California African American Museum, reads as a visual manifesto on Malcolm X. But beyond homage, Erizku asks uncomfortable questions: What do we do with icons once absorbed by the mainstream? How can we reinfuse them with radical energy? His answers aren’t literal — they’re symbolic, crafted through unexpected materials, luminous installations, charged objects, and immersive soundscapes. Everything in his work feels ceremonial.

What makes Erizku particularly compelling is how he fuses the spiritual with the aesthetic without falling into cliché. His studio —a minimalist cave infused with incense, open books, and drifting hip-hop samples— feels more like a sanctuary than a workspace. “I’m not just producing images. I’m constructing a language that invokes and resists at once,” he explains.

One of his most talked-about works is his reimagining of Nefertiti: the classic bust transformed into a disco ball. Sacred and pop collide boldly. “A lot of these symbols were co-opted, stripped of meaning. I want to give them their power back,” he says. Under his gaze, Afro aesthetics aren’t a trend — they’re a form of resistance. A living memory.

In a world overloaded with imagery, where algorithms determine what we see before we even want it, Erizku’s art slows things down. It demands to be processed, felt, and witnessed. Amidst the rise of AI-generated content, his work feels more human than ever. “Oversaturation will bring us back to the handmade. People are searching for soul, even if they don’t know it yet,” he notes.

And he’s right. There’s something deeply tactile about his art. As if each piece carries fingerprints. As if every sculpture, photograph, or installation whispers something old, aches with the present, and looks fiercely forward. The influence of fashion —and its narrative power through body and image— is also present. His work could live as easily in a museum as in the pages of a high-voltage fashion editorial.

At a time when visuals are fleeting and disposable, Awol Erizku offers something else: symbolic density, uncomfortable beauty, layered truths. His work isn’t designed for likes — it’s made to linger, like a question with no easy answer.

More than an artist, Erizku is a conduit. A voice translating the ancestral into something unapologetically current. His practice isn’t about nostalgia — it’s a future built from the invisible fragments of a past that still burns.