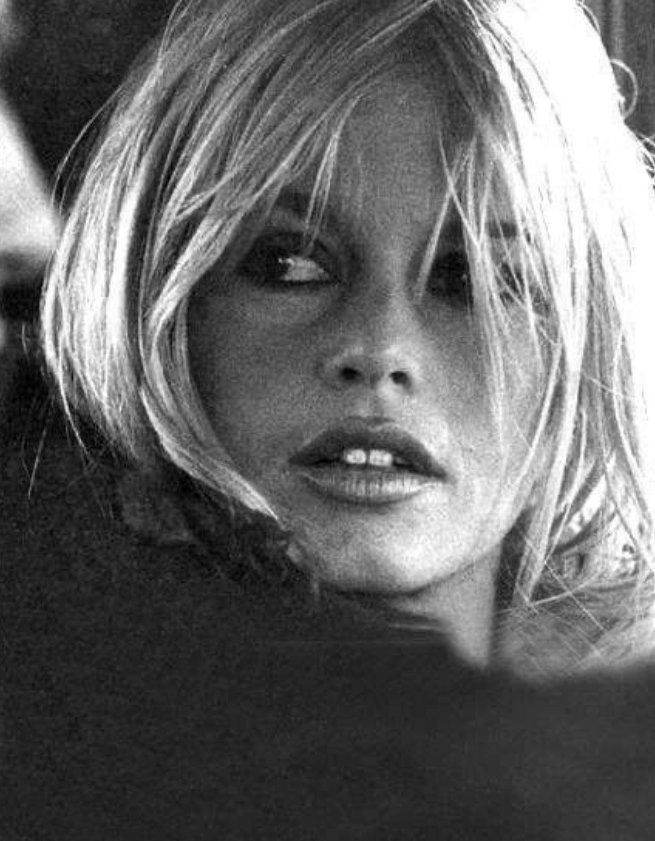

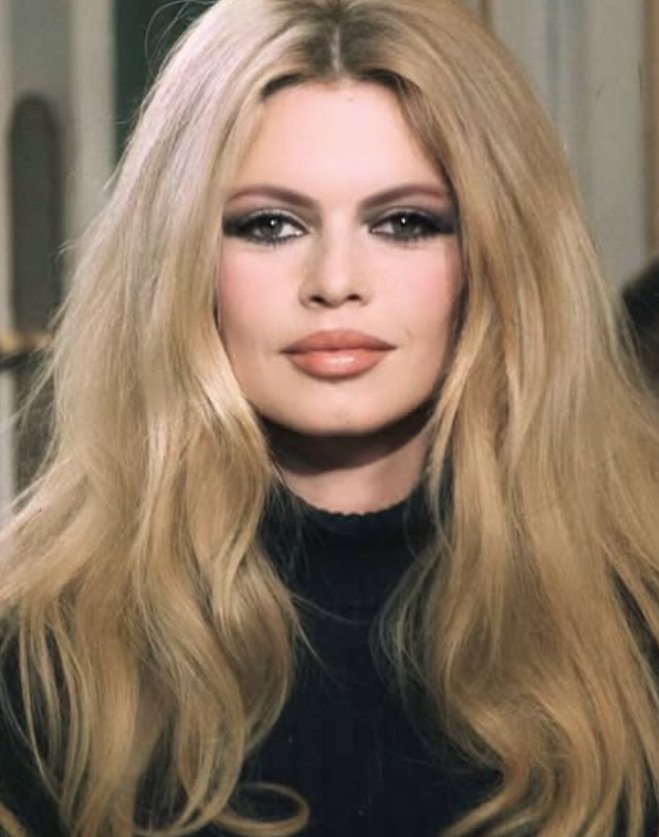

Had she not always resisted being boxed in as a mere “object,” Brigitte Bardot might be described as one of France’s most successful cultural exports of the twentieth century. After “And God Created Woman” in 1956, her sudden international stardom turned her into a symbol of erotic upheaval, a face that condensed youth, appetite, and defiance into a new cinematic grammar.

That visibility reached a paradoxical peak in 1969, when her features were chosen to model Marianne, the allegorical embodiment of the Republic. Bardot’s likeness appeared on statues, stamps, and coins, fusing popular desire with national iconography. Yet celebrity never fully owned her. At thirty nine, at the height of her fame, she abandoned cinema altogether, redirecting her notoriety toward animal rights, from seal hunts to slaughterhouses, with relentless fervor.

For three decades, Bardot also represented an anomaly within French culture: a superstar who openly embraced the far right. Convicted multiple times for inciting racial hatred, she aligned herself with a known past and present vision of France shaped by fear of immigration and witch hunts to anything that wasn’t animals. Her marriage to Bernard d’Ormale, a confidant of Jean Marie Le Pen, formalized that ideological turn, placing her alongside figures like Alain Delon in a mythologized lost golden age.

What made Bardot uniquely troubling was not provocation alone, but the collision between her earlier image and her later speech. Once hailed as a personification of female freedom, she crossed, after leaving film, into overt Islamophobic rhetoric, confusing rebellion with exclusion. Admirers and detractors alike struggled to reconcile the woman who shattered sexual conventions with the celebrity repeatedly fined for intolerance.

Long before this contradiction hardened, Simone de Beauvoir perceived Bardot as a natural force. Writing in the mid nineteen sixties, she argued that Bardot’s screen persona obeyed inclination instead of rules, stripping morality of its leverage. Desire, movement, and appetite defined her presence.

Retiring in 1973 before turning forty, she nonetheless remained unforgettable. Her life traces the fragile boundary between emancipation and transgression, reminding us that freedom, when detached from solidarity, can harden into something terrible.

Reactions to her death revived these debates, exposing how memory edits complexity. Celebration and condemnation coexist uneasily, mirroring a society that still negotiates its dark past, identity, belonging, and the dark side they don’t want to admit. Bardot endures less as consensus than as a provocation, asking what France chooses to admire, forgive, or refuse today publicly again.